Orthodoxy & Orthopraxy: Together at Last

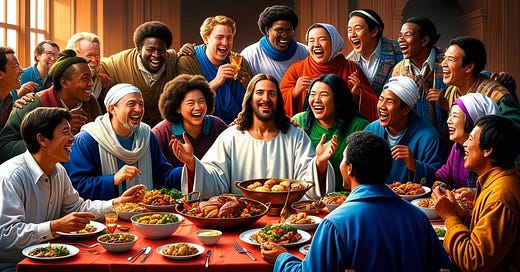

God’s table is wide, wild, and wonderfully strange — a place where holding tension may be the only way to see the fullness of beauty.

Some people might think I’m wishy-washy when it comes to theology because I don’t land cleanly on one side of many issues Christians debate these days. It’s not that I don’t have opinions (I have plenty!); it’s that for most of my life, I’ve been highly aware of what it feels like to be left out.

This is not because I have always been excluded. That’s a whole other level of terribleness that all too many people DO experience!

Rather, it’s because God wired me this way.

I see the person at the edge of the room, alone. I notice the person at the table who has been silent the entire meeting for fear of speaking.

So when theological conversations arise, I often find myself asking, “Who gets left out if we believe this?” I tend to see multiple sides, because I’m always scanning the room, wondering who’s not being invited in.

That posture can make me look, well… waffle-y. Conservative Christians think I’m too progressive. Progressive Christians think I’m too conservative. I’m like a slightly defective puzzle piece—still part of the picture, but not quite snapping into place.

Because of that, I’ve carried an ongoing, inner conversation about two quirky little words: orthodoxy and orthopraxy. One means “right belief.” The other, “right practice.” Belief and action. Theology and embodiment. Doctrine and fruit.

When the Framework Shifted

Growing up Catholic, I believed faithfulness meant getting things right—right beliefs, right answers, right theology, right behavior.

I held orthodoxy like a compass, certain it would always point me toward God. If I could just stay inside the lines—believe the right doctrines, avoid the wrong books, trust the approved voices—then I’d be safe. Then I’d be faithful. Then God would be pleased with me.

Over time, though, and I am entirely unsure of when, that framework shifted.

It wasn’t a loud rupture. It was like moments of tension and inner struggle and noticing how sometimes “right thinking” seemed to usurp a way of living that felt more like how Jesus lived.

As I studied more deeply and spent time in graduate school, I began to ask things like: Why are the kindest people I know not at the theological table? And, Why do some Christian spaces feel more like gated communities than places of grace and welcome?

I began to notice how narrow the table had become. The guest list had been curated and the conversation, policed! And I began to wonder if the Jesus who welcomed children, tax collectors, women, doubters, and sinners would even recognize the Christianity I was seeing around me. I still often wonder this when I am in certain circles.

When the Table Gets Too Small

The word orthodoxy comes from the Greek orthos (right) and doxa (glory or belief). It refers to the essential teachings of the Christian faith — like those found in the Apostles’ or Nicene Creed. For centuries, these creeds have grounded the Church and clarified who we are and what we believe.

But orthodoxy didn’t arrive fully formed. Church historian Justo González reminds us that doctrine was shaped in real time — through councils, arguments, and yes, politics. When Constantine convened the Council of Nicaea in 325, it was partly to bring theological unity — but also to stabilize an empire.

There is deep beauty in orthodoxy. I still find comfort in reciting creeds. I still treasure words like, “very God of very God, begotten not made.” But somewhere along the way, orthodoxy also became a litmus test for belonging — a boundary line more than a foundation.

And when we use it that way, we stop hearing vital voices — voices from the margins, the deserts, the prison cells. Mystics, prophets, women, enslaved people, Indigenous Christians — those who may not have shaped the creeds, but have helped shape the Church.

Willie James Jennings puts it bluntly: Western Christianity often built its theological tables in halls of power — deciding who got a seat, who had to serve, and who was left outside, hungry and unheard. This is sad to me.

What Good Is a Right Belief Without Right Living?

That leads to another word we don’t talk about enough: Orthopraxy, which means “right practice.” If orthodoxy is about what we believe, orthopraxy is about how we live.

You can affirm every line of the Nicene Creed and still be unkind. You can quote Calvin and Barth and still ignore the poor. You can win theological arguments and still miss the face of Jesus in your neighbor.

And on the flip side, I’ve met people who no longer attend church or struggle with belief — but who live with stunning gentleness, generosity, and humility. Their lives reflect Christ more clearly than many who claim doctrinal purity.

James Cone, the father of Black Liberation Theology, once wrote:

“The truth of the gospel is found not in abstract propositions, but in the lives of those who bear witness to it in the midst of suffering.”

Orthodoxy in itself isn’t the problem. At its best, it gives us language for the mystery of God, a shared foundation across centuries and cultures. I still hold to much of it with reverence!

But when orthodoxy becomes a gate instead of a guide — or when it’s used to keep out those whose lives clearly bear the fruit of Christ — it’s worth asking whether we’re truly honoring the spirit behind the words we so carefully defend.

God's Table Is Bigger Than We Think

I’ve come to believe that God’s table is bigger — wider, wilder, and more wonderful — than the one many of us were taught to protect. It doesn’t just accommodate the expected guests; it expands beyond what feels comfortable and safe. The table groans under the weight of its generosity, stretching across divides we didn’t think could be crossed.

And there’s always one more chair! (Of course, I’ve written about this before, and I will again.)

It’s not a table reserved for the certain or the pure or the theological elite. It’s a table set with broken bread and poured-out wine, where grace is served in second helpings and no one goes home hungry.

It is good news!

And over the years, I’ve come to see this table all throughout Scripture:

The Samaritan Woman at the Well (John 4):

She’s a woman, a Samaritan, and living a life that would have made her an outsider by any first-century Jewish standard. And yet Jesus doesn’t avoid her — he engages her in one of the longest theological conversations recorded in the Gospels! He offers her dignity, agency, and living water. And then — remarkably — he entrusts her with sharing the news of who he is. She becomes the first evangelist to her village, not after she “gets it all right,” but simply because she was willing to receive what he offered.Zacchaeus the Tax Collector (Luke 19):

Zacchaeus is a collaborator with Rome, a cheat, and likely hated by his community. He doesn’t ask for a second chance — he just climbs a tree to get a better look at Jesus. And Jesus, seeing him, calls him by name and insists on coming to his home. It’s the table first — fellowship first — before repentance, before restitution, before any theological realignment. In that shared meal, something changes. Grace goes first, and transformation follows.The Thief on the Cross (Luke 23):

He has no record of right belief, no time to reform his life, and nothing left to offer but a desperate plea: “Remember me.” And Jesus, in his final breaths, welcomes him with astonishing immediacy: “Today you will be with me in paradise.” Wow. Wow. No doctrinal quiz. No purity test. Just presence, mercy, and a place — at the very last possible moment — for someone the world had already discarded.

Jesus keeps setting tables no one else would set. And he keeps inviting the very people others overlook. It’s a little bit ridiculous. And it’s good news.

An Attempt to Sum This Up

I care about theology. I deeply value the wisdom passed down over generations. But I no longer believe that right belief is the whole of faithfulness.

Faithfulness in the Christian faith is footnotes + fruit. It’s the structure of an argument + the shape of life. It’s trying to explain things like “hypostatic union” + trying to sit with someone you think isn’t a Christian because they don’t look like you.

Jesus said, “By their fruit you will know them.” Not by their systematic theology or their church attendance.

Today, I hold orthodoxy gently in one hand even as I continue to balance orthopraxy in the other. I hold tradition and I allow for God’s Spirit to widen my awe of him.

I think what it means to be a Christian today includes setting long tables and being uncomfortable and admitting when we are wrong or don’t know.

As I try to sit at the table with Jesus, I look around and see a lot of people with a lot of different ways of seeing this world. Some of them make me want to draw closer, while others make me stress eat crackers.

But here I want to stay because no one should ever be without a seat at the table. If they want to sit with Jesus, who the heck am I to say they aren’t allowed, after all?

Cheers to being waffle-y for the sake of God’s one, big, beautiful table!

❤️ Much love,

Laurie

This, Laurie. All of it! You have articulated once again my struggle since 2009 when my husband lost his job and our primary income after 29 years of faithful service at the hands of evangelical Christians. And then the 2016 election. I have struggled for years and years with trying to be good enough for their club, and now I am aghast at how unwelcoming and narrow their table has become. I am hanging onto Jesus.

Amen sister.... Somehow we "Christians" have recently defined what are absolutes and what we are to believe.

Personally, I find myself staying silent as I listen to forceful thinking that I frankly don't believe or agree with.

I've often felt like I didn't want to be identified with "Christians" because their actions don't reflect Jesus' message. A message of love, patience, understanding, empathy, caring and self-lessness.

Can't I be Christian without aligning myself with the current agenda?

I believe I can.